Until the mid-nineteenth century when Canadian artists were inspired by the European impressionists, art in Canada was known for works by local illustrators and its indigenous peoples. These works often imitated the sublime portrayals of grand American wilderness landscapes. However, the most influential and distinctly Canadian art was not a moment of Europe’s leading artists, but instead grew from the seeds of its very own inhabitants who wished to visually document the land’s dramatic vistas and silent places of refuge. Those artists, who eventually solidified as ‘The Group of Seven,’ did not plan a Canadian panorama from the warm cracking fireside comfort of a studio, but instead trekked the thick forested hills and ravines through weeks of outings to explore and record landscape as it occurred. Left in their intrepid wake, the country benefited from thousands of sketches, watercolors and soulful representations of the land that was rarely seen by man.

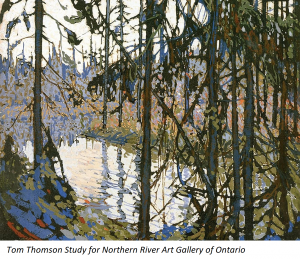

In the early twentieth century the popular Algonquin Provincial Park, a three thousand square mile fish and game preserve in Northern Ontario, could be reached by a 125 mile train ride on the Grand Trunk Railway from Toronto. Visitors anxious for a fishing and canoe ride cure from their daily routine, hiked the distance as a rustic antidote to the stress of city life. One lodging, located at the end of a long train line, Hotel Algonquin at Joe Lake Station, offered seventy-five rooms and promised indoor hot and cold running water, with a warm meal. Two visitors to the area in 1912, Tom Thomson and Harry Jackson, chose instead a more economic stay at the barracks of an abandoned lumber mill in the village of Mowat, near the town’s favored Canoe Lake. With fishing poles in tow and modest art supplies Thomas and Jackson began a journey that would fuel the imaginations of Canada’s ‘Group of Seven’ artist for years to follow. Navigating the lake and hiking the area for weeks at a time the young men would risk frostbite, curious wildlife, bears, and hunger that took ‘en plein air’ painting to the level of an extreme sport.

Thomson and Jackson had met prior to the first world war at Toronto’s Arts & Letters Club, a gathering place and outlet for artists, writers and creative spirits. Among the members was a small group of illustrators who at the time were working in studios and commercial art for the area’s leading manufacturers. Five of the members Franklin Carmichael, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley worked at Grip Limited, a Toronto based design firm. The popular Arts and Letters Club became a regular meeting place for discussions over meals, creative activities and encouragement. It was at the club that they first planned en plein air outings to commune with Canada’s vast country side through their art.

By 1914 the small group of artists built a community studio at Toronto’s Rosedale ravine, provided via the financial support of group member Lawren Harris, heir to the Massey-Harris farm machinery fortune. The building quickly became a well-loved meeting place and general exhibition space until the First World War when the informal gatherings splintered as members Jackson and Varley left to become official war artists. After the war, the club reconvened for planned outings and began to exhibit in local organized shows. Their public presentations grew popular as images of the artists’ unflinching devotion to Canada’s vast landscape, revealed the country’s depth and untapped potentials.

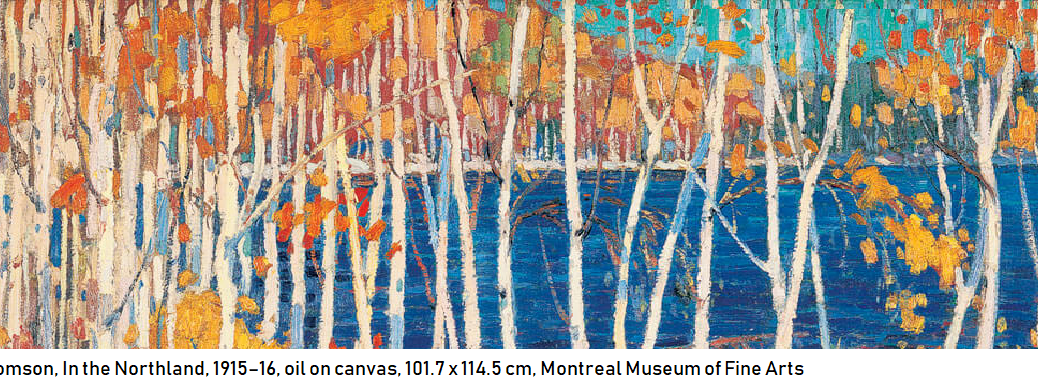

Venturous art pioneers, the Group of Seven marked Canada’s budding modernist art movement led by artist Lawren Harris (1885-1970). In 1918 Harris traveled to the Algoma region with friends MacDonald and Johnston and later made his first trip to the North Shore of Lake Superior in 1921. Harris painted abstracted vistas that did not tell a story of the land, but instead explored the metaphysics of a painted landscape. His images of the cold and empty northbound territories with isolated peaks, and limitless dark lakes may at first appear contemporary, but were actually surreal impressions, iconic snap-shots of the country’s deep interior. As seen in a catalog or reproduction, Harris’s work’s appear as simple studies in blue and white. However, on the rare opportunity to view original works the canvases range in unexpected blues, greens and blacks through subtle, but effective value changes. Incremental color gradations reveal Harris’s mastery of changing light and attention to atmospheric detail.

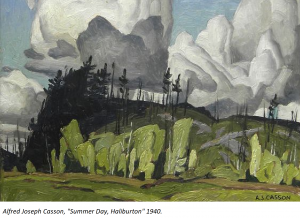

Today, Harris and The Group of Seven are Canada’s most famed art explorers, their works have come to represent the country’s rugged wilderness as recorded through their personal iteration travel and painting styles that chronicled the diverse wilderness.

In closing this first part of TheArtGuide.com’s Canadian art series, it should be noted that Tom Thomson is often considered an original member of The Group of Seven, and though a friend and artist, he died prior to the group’s official founding, in 1917. The mysterious surroundings of his death at the Algonquin Park, Canoe Lake in 1917 became the source of Canadian ‘art lore’ – even today a Twitter account, @TTLastSpring, was created to retrace Thomson’s final months. Another strong influence in the club’s identity was Emily Carr, welcomed to the group by Lawren Harris, noting “You are one of us.” A statement that ended her art study isolation of the previous 15 years and lead to Carr’s most prolific run of works.

Coming soon in Part Three of this series, TheArtGuide.com takes a look at the background and experiences that encouraged these young adventurous artists to chronicle Canada’s unseen wilderness.