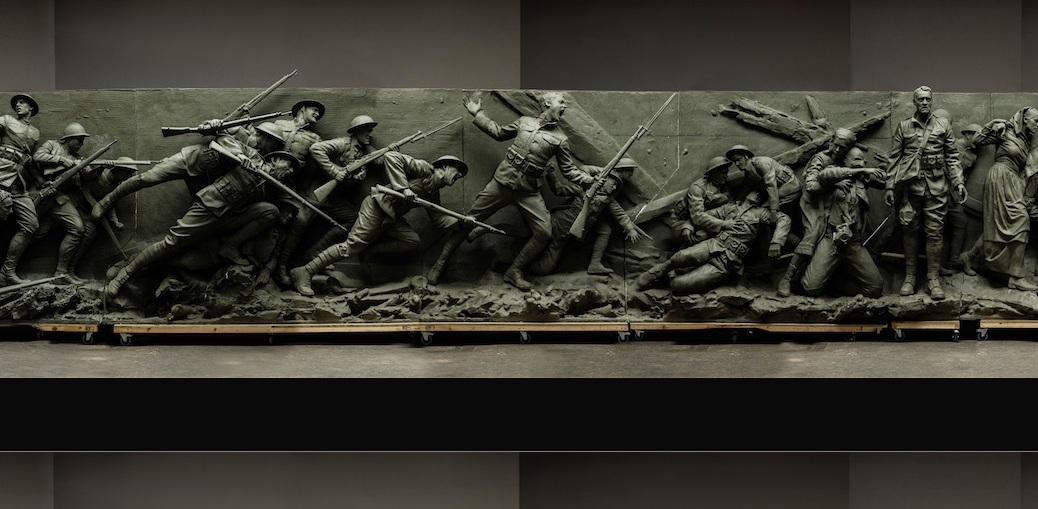

A dramatic high relief bronze sculpture titled, A Soldier’s Journey, by sculptor Sabin Howard commemorates the first World War One monument in Washington DC.

Last Friday night as evening fell on the busy streets of Washington DC, The WWI Centennial Commission and The Doughboy Foundation unveiled a new 60 foot bronze war memorial of thirty-eight individual figure in a five panel narrative. An illumination ceremony of military fanfare and US Army Band ballots was visited by dignitaries who shared heartfelt speeches of remembrance as the newest city monument was officially turned over to the Washington Parks Department.

The dramatic high relief bronze World War I memorial titled, A Soldier’s Journey, by sculptor Sabin Howard presented viewers with an essay in opposites; contrasting a young girl to men at war and the customary stillness of a water pool to the sculptured turbulence of battle charging infantry in arms.

An Heroic – Historic Undertaking

The memorial and surrounding DC park site plan first began over nine years ago by The WWI Centennial Commission. In remembrance of soldiers and battles fought during that war, the organizers simply tasked competing design teams to consider, “something memorable, that will inspire citizens to learn more about the war and our nation’s history.” Their competition selection resulted in a young architect, Joseph Weishaar (b. 1990), and seasoned figurative sculptor, Sabin Howard. The design team’s plan focused on a 58-foot linear bronze work as the centerpiece of then Pershing Park, and prominently located next to the White House lawn, at Pennsylvania Ave and 15th Street. The city site plan occupied a 1.7 acre area, of monumental sculpture, fountain feature, two ten-foot granite information walls, belvedere, public seating and reflecting ponds.

Tranquil Tree Lined Setting

The WWI Commission accepted the architectural design proposal for then John J. Pershing park, was notable in that Joseph Weishaar had little work experience and at the age of twenty-five, was an intern – not yet licensed a architect. The firm of GWWO Architects in Baltimore stepped in to help oversee Weishaar’s site development and construction. It interested the commission that Weishaar’s design specification stipulated a ‘figurative monument,’ in lieu of modern conceptual works. From the agreement, a new collaboration of architects, artist and land developer resulted in a balance design of minimal modern plaza to showcase a traditional work of sculpture. Their plan introduced new elements of two ten-foot engraved granite information walls and a belvedere to quickly read over a setting of low rise stepped stone seating, walkway, sculpture and reflecting pool. To the opposite side the granite presentation wall is the Peace Fountain waterwall, with raised text excerpt from the poem “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak” by Archibald MacLeish, which begins;

-

-

- “…They say, We were young. We have died. Remember us.

They say, We have done what we could but until it is finished it is not done…

They say, We have given our lives but until it is finished no one can know what our lives gave.

They say, Our deaths are not ours: they are yours: they will mean what you make them.”

- “…They say, We were young. We have died. Remember us.

-

The raised plaza and circular belvedere artfully incorporates information plaques and engraved titles of WWI campaigns. It also provides a view over the lower level bronze centerpiece and granite walks. Bermed earth with foliage surrounding the stepped granite seating areas reduce pedestrian noise and act as a city sound barrier. The simplicity and smart design of Weishaar’s masterfully planned plaza cannot be underrated in it’s ability to meet design criterion in a remarkably tranquil inner city space.

Follow the Enlisted Guy

Sabin Howard’s described the WWI monument, A Soldier Journey as a personal service to the military and public. Presenting only one soldier’s war experience, it is Howard’s hope to represent all American veterans and active duty. His design proposal for the World War I Centennial Commission was a sobering one; to create a narrative representing 4.7 million enlisted service members and over 116,000 who gave their lives. He distills the experience of many through the events of one soldier shown in five scene panels across a 58-foot length transition and 38 individually designed life-size figures.

Cast shadows of sunlight animate Howard’s bronze high-relief figures that seem to show momentum across the 58 foot linear plain. Five themed panels take the journey of just one WWI soldier, from initial recruitment and departure, to an awaiting fellow infantry in the midst of battle. Carved into each of the figures is a unyielding sense of drama. Howard’s work does not ignore the severity of or embellish war, but instead offers ownership to it. The momentum of his visual narrative ends with a silent victory, marked simply by a young girl reading her father’s discharge papers. The message Howard wove through his many bronze figures is clear to all service members; lives were disrupted, men were lost, many left home without assurance of a plan for return to safety.

“Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction.” Ronald Reagan